We want to work with early-stage startups in fintech, even though they may compete against some of our members”

The above comment was made by Louis Levesque, CEO at Finance Montreal, at the opening of the 6th Canada Fintech Forum on the 30th of October this year. For us at FormFintech, an organization that is involved with fintech startups at the grassroots level, this was not only heartening to hear but also a testament to the changing mindset when it comes to collaboration between startups and incumbents in the financial services industry, along with the growth spur that Canadian Fintech has experienced in the last 5 years.

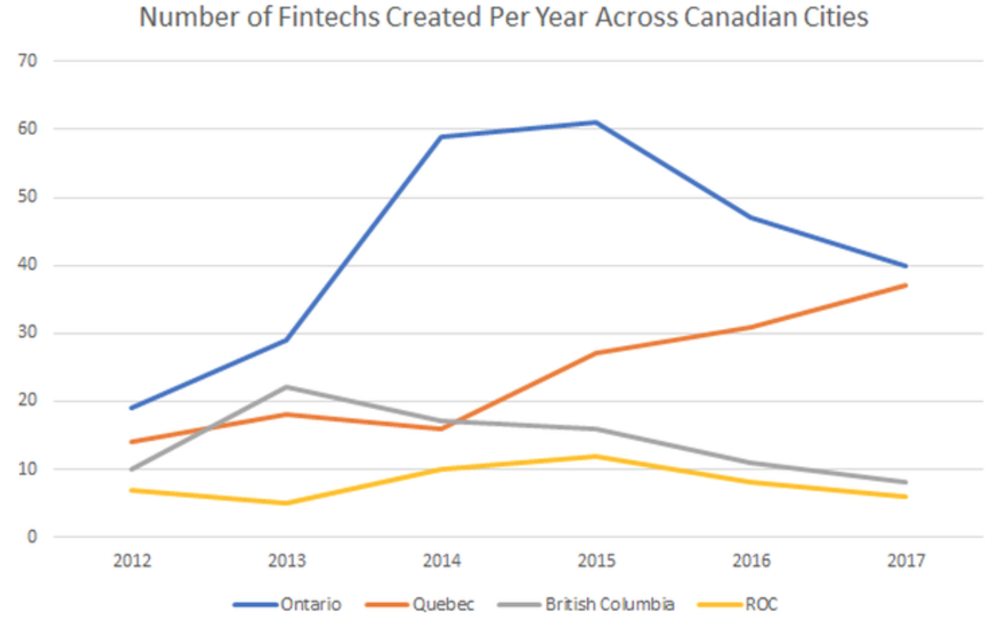

FormFintech recently completed its first iteration of the Canadian Fintech Ecosystem. One of the major deductions from the analysis of the data collected is congruent with the notion that fintech is gaining traction in Montreal and Quebec.

More specifically, the number of Quebec fintech startups created per year has witnessed an almost two-fold increase since 2014. In addition to that, a couple of major ecosystem players, namely the Holt Fintech Accelerator and Luge Capital, came into existence this year; further strengthening Montreal’s fintech-backbone. Finance Montreal’s upcoming Fintech station will add to Montreal’s firepower, putting the city on the map as a complete and cohesive unit that caters to all the needs of a fintech startup.

There is, however, a caveat here. Even though Quebec is experiencing a fintech revolution, there has been a cool-off in the rest of Canada, namely Ontario, which saw a peak in fintechs created at 59 in 2014, followed by a steady drop to 40 in 2017.

This could mean two things, either the Canadian fintech ecosystem is maturing and moving towards consolidation, or that it is losing steam. Some point to a third possibility: fintechs operating in stealth mode with complete focus on product development, before coming out in the open with a bang!

Only time will tell as to what the real reason is, but given that banks are increasingly jumping on the fintech bandwagon, our money is on maturation and consolidation, which is good news as it means a higher proportion of fintech startups with better-defined products and markets that are also more stable.

The Base Ingredient

The base requirement for a strong early-stage startup ecosystem is a low barrier to entry. If a group of enthusiastic college kids cannot build a product in their dorm room, the tech sector under question will witness a slower than ideal progression.

Since fintech is a derivative of the finance industry, which is data-driven to mammoth proportions, an effective method to accelerate the development of startups is easy access to data. In other words, open banking – which was a common theme among all topics and discussions in and outside the forum. We, thus, decided to cover the fintech forum through the lense of open banking.

Specifically, what steps did the banking industry go through to reach open banking, the state of open banking across different countries, recent developments in Canada – indications for the future and stakeholders, liability sharing and challenges involved.

Stages before ‘Open Banking’

Open banking primarily depends on the basic premise of data portability. In an ideal situation, complete data portability would entail that users have control over all their data, plus the flexibility to use it as and how they see fit.

No country, at present, is at that stage of ‘absolute’ data portability. For instance, Europe started experimenting with an open payments data system in the year 2009 and is currently in the process of tackling issues related to integration of countries outside Europe. Australia, on the other hand, recently took the first step towards an open banking regime, with the introduction of a new regime that would force big four banks to open their data by July 2019. Similar initiatives are underway in Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, UK, etc.

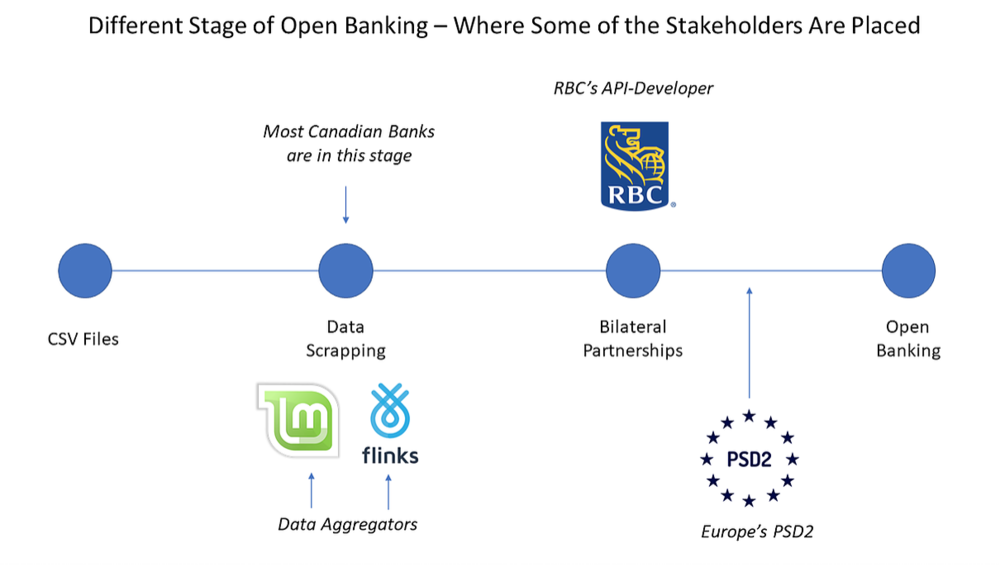

Within countries different financial institutions (FIs) are at varying stages of data portability. An analysis of these stages will allow us to better understand the process of open banking evolution.

The first stage involves the use of CSV (comma separated values) files as the primary mode of data transportation. In this case, the bank’s staff would be able to share data among themselves, but the end-user may not have access to this information.

Data scraping is a step above CSV files transfer, the modus operandi of most data aggregation startups within and outside Canada. With screen scraping, a piece of software “mimics” a user and logs onto the system on her behalf. Following that, it extracts the user’s banking information and stores it on a database which can be used by a third-party provider (TPP).

Bilateral partnerships are the next stage on the open banking chart of evolution. As the name suggests, bilateral partnerships involve the sharing of data, revenues and liabilities between banks and startups. Royal Bank of Canada’s developer-API initiative can be categorised as a bilateral partnership.

RBC’s developer-API and bilateral partnerships in general, however, has a major drawback. Especially for startups because financial institutions have control over data and can pick-and-choose which parts to share, how to share and when to share.

That being said, bilateral relationships serve as an excellent “experimentation” phase for banks, through which they can develop the confidence, processes and assets needed for a complete open banking environment.

Stakeholders, Liability Sharing and Challenges Involved

Regulatory authorities, consumers, Fis and TPPs are the primary stakeholders in most discussions pertaining to open banking. And conversations usually revolve around the topics of data privacy, security, cost distribution and competitive landscape. Cost is the most easily understood concept among these topics, so we will begin there.

At the first open banking panel discussion at the Fintech Forum, one of the panelists stated that the up-front cost of an open-banking ready system for a FI is close to $200 MN. That, combined with the tax costs incurred on each data pull, serves as a plausible detriment for banks to take a plunge into the open data landscape unless the competition and consumers really demand so.

Liability is another issue that banks grapple with when deciding whether to play offense or defense in the open banking game. Ever since the advent of modern banking, financial institutions have been the custodian of consumer data, along with gathering data around the customer, in addition to exploring the nature of their relationship with the bank. But all this changes in an open banking system because customer information is shared with TPPs through a chain of nodes (connecting points among various systems), leading to increased vulnerability and security concerns.

As Sairam Rangachari, Global Head of Open Banking at JP Morgan, rightly said, “If there were a data breach tomorrow, the headline won’t read startup XYZ got hacked but rather JP Morgan got hacked. Even if the breach may not be completely the bank’s fault.” It’s a matter of couple of rogue nodes for the entire system to get a bad rep, causing the general consumer to lose trust in the system. On the flip-side, Yves Gabriel, CEO and Founder at Flinks, mentioned that innovations will be stifled if people keep yelling “security, security!” everytime we try to take a step towards an open banking environment.

Even if we were to table the issue of security and assume data breaches as a non-issue, privacy concerns rise up to the surface. Access to someone’s bank account does not only allow one to conduct criminal acts associated with data theft, but also gather intimate details on an individual.

Mechanisms that delete user data after use could to put in place to respect the consumer’s “right to be forgotten.” In other words, any TPP that uses a consumers data should delete it immediately after use. Even “at rest” data i.e. data stored on hard drives, which could eliminate concerns about who is storing and using the user’s data and for what purpose.

To tie all together, it is safe to say that FIs and TPPs need to spend considerable amounts of time, money and effort to chart out effective authentication controls, clear policies pertaining to data governance and security; along with reporting, response and mitigation processes in case of cyber attacks. Which really begs the question: why do we need open banking to begin with?

The answer was somewhat touched upon in the second open-banking panel. If we were to use the consumer’s interest as the north-star, it becomes clear that we should move towards an open-system because that would lead to acceleration of innovations in the finance sector ie. it will be easier for small startups to create products that satisfy needs of the consumer.

And an enhanced customer experience is something that is really needed. In fact, an innovative bank such as Tangerine has been beating its brick-and-mortar counterparts consistently over the past 6 years, according to a survey carried out by marketing information services firm J.D. Power, which serves as proof that traditional banks are anything but customer-centric.

At this point, if you are thinking that the topic of open banking isn’t as black-and-white as it seems to be, you are not alone. Which is why regulatory authorities and governments need to step-in, with the aim to create the right governance framework that would enable innovations without putting consumer data at risk. At the panel, Lionel Pimpin, SVP for Digital Channels, Retail and Commercial Strategy at National Bank of Canada, confidently stated “…if we have the right governance as the base, everything else falls into place.”

Canadian regulators definitely agree, which is probably why the AMF – the financial regulatory authority in Quebec – recently created a Technological Innovation Advisory Committee and minister Monreau launched an advisory committee on open banking.

Conclusion

One question was common among all discussions throughout the forum: Would Canadian banks see open-banking as an opportunity or threat? With recent developments made by RBC and Desjardins’ Open Data Challenge, one can say that there is move towards open banking. But will they stop there?

Fast forward into the future with a full open-data environment, and we are likely to see a platformification of financial services through intensified product competition. Put differently, the bank client of the future will likely have a store full of fintech apps on his mobile phone, and only those apps that speak to the consumer at every level would survive.

For the incumbents, the winning side will include those that focus on developing flexible core tech infrastructure which can adapt to changing technological landscape; have the necessary “catchers” to collect data from varied and multiple sources, inculcate the ability to produce actionable insights and develop cultural change that leads to customer-centric product development. But does this mean that banks will eventually try to become a fintech themselves, causing smaller players to exit the market? Nobody has a crystal ball that can predict the future, but FormFintech recently completed a preliminary analysis of fintech-related actions taken by Canadian banks over the past 5 years.

Articles following this fintech forum and open-banking coverage will focus on those topics – which could shed light on their future course of actions. If you are interested in staying informed, please sign up for our newsletter below.

If this article was of interest and you want to learn more about fintech in a formal setting, check out our upcoming fintech certificate here.