Trouble in the Blockchain-Carbon Trading Paradise

Following the success of the Acid Rain Program, an emissions trading system (ETS) was considered as the ideal solution to tackle environmental pollution. The first part of this article series assumed that emissions trading is the quintessential way to control GHG emissions.

But it would not be far-fetched to say that cap-and-trade has largely been ineffective. Largely because the resultant low carbon prices have not served as a formidable deterrent for big emitters. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation & Development, Carbon prices are about 80 percent lower than what they should be to protect the climate.

Furthemore, a carbon price floor (a minimum price for each carbon unit traded) may not be sufficient as ETS has many other problems, three of which are mentioned below:

1. Most projects are not really “additional”: A project is considered additional if it would have not happened otherwise i.e. decreasing carbon emissions was the main reason behind the commencement of the project in question. However, most clean development projects (CDM) in developing nations cannot be considered additional.

Simply put, these projects would have been undertaken irrespective of their effect on the environment. The credits that these projects receive are, therefore, not really carbon offset in the purest sense.

2. Corruption and non-transparency: Many projects are marked as CDM even though their positive effect, or the lack thereof, on emissions reductions is questionable.

For instance AT Biopower, a Thai company, started using rice husk to generate electricity, qualifying it as a renewable electricity source and thus, earning carbon credits.

What everyone failed to mention was the fact that these rice husks had for long been used by farmers as a form of fertilizer. In the absence of rice husks, farmers had to resort to petroleum-based chemical fertilizers, which are a form of pollution. Even though the primary project led to carbon reductions, environmental pollution as a whole did not change significantly.

3. Political influence: Caps in emissions trading are set and distributed by the government. This scenario creates the possibility for endless political lobbying, results of which have been highly detrimental to the carbon market.

Due to these political meddlings, the price of carbon has hovered around $10 per tonne, which as discussed before is well below the level needed to reduce emissions.

Carbon Taxes

Carbon taxes, at first sight seem like a plausible solution to these ETS problems, but they too have certain serious limitations – cross border competitiveness being the biggest.

The example of British Columbia’s tax on the cement industry serves as an excellent illustration. In this case, a carbon tax caused the BC cement industry to reduce emissions and suffer because imports from China and the US were not taxed. BC’s local industry reduced emissions, but the amount of cement used on a global-scale and therefore emissions did not change.

All this is to say that if carbon taxes are not binding worldwide – eliminating the possibility of cheaper imports produced by polluting manufacturers – there will not be no overall reduction in emissions.

Other problems associated with carbon taxes:

Industry Specific

Carbon taxes do lead to reduction in certain sectors that are specifically targeted by the said tax, but have no effect in other industries. For instance, if the cement and oil industries are taxed, there will be reductions in those sectors but electricity, heat, transportation etc will continue to pollute.

Implementation Problems

Canada’s decentralized approach to a carbon tax recently came under fire by the OECD for being overly complicated and difficult to implement. The OECD emphasizes that a lot of work will be required to measure provincial cap-and-trade systems against the federal benchmark. Additionally, each of the provincial plans have many differences – including those based on price and products to be charged.

Politically Influenced

Last but not least, carbon taxes are subject to the whims of the political administration in power. One party may impose a carbon tax, while the next might rescind it. A less than ideal situation, given that there needs to be consistency over several years for meaningful reductions to take place.

Carbon Sequestration to The Rescue

All these seemingly ghastly problems can be solved through carbon sequestration, an artificial or natural process where carbon is removed from the atmosphere using devices known as carbon sinks, and stored in liquid or solid form.

For those who have been following developments in carbon markets, this may sound reminiscent of carbon capture and storage (CCS), where carbon is captured and stored in the ground – a concept that has not gained traction because it is incredibly expensive.

This concept, however, gains new meaning when stored carbon is used for commercial purposes. Possible if it is in liquid or solid form – a process called carbon capture and use (CCU).

In fact, gaseous carbon is being used to make polyurethane foams for seat cushions or carbon fiber (which costs less as compared to using polymers). Also, carbon can technically be converted to any type of fuel and used as a binding agent in concrete.

CCU combined with the extended expertise of aspiring blockchain wizards can provide a framework that is robust, scalable and multinational.

In this setup, every entity that emits carbon would pay for it through a carbon coin, and every time an entity sequesters carbon, it would receive a carbon coin. In an ideal situation where all coins are sequestered, the world will be run on zero-carbon emissions.

Can Blockchain Be The Successful Lone Wolf?

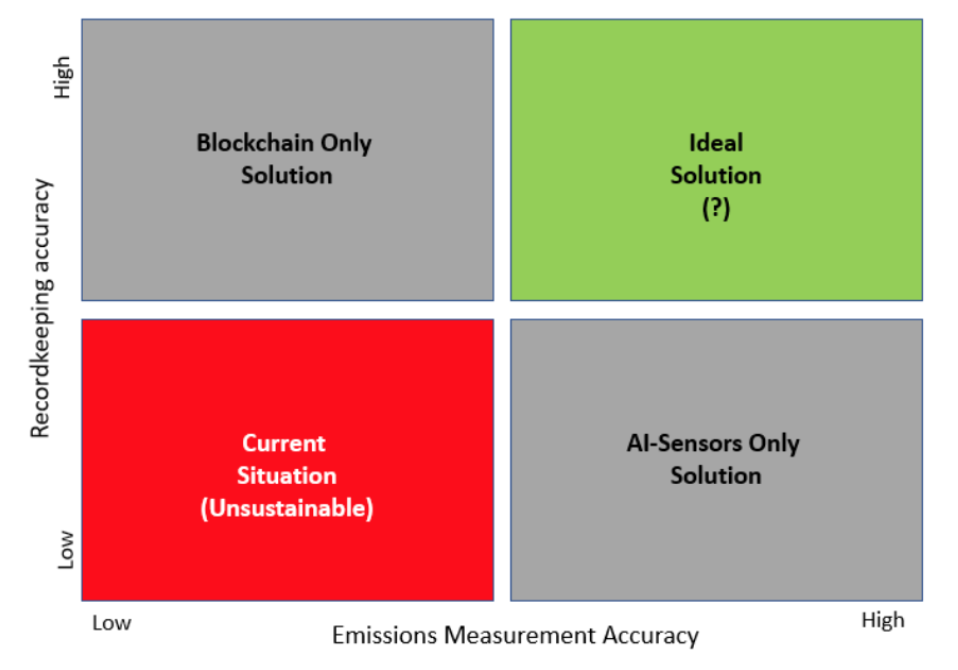

At this juncture, blockchain enthusiasts would be ready to make an unambiguous declaration stating that the technology has the wherewithal to completely alter the face of the carbon trading landscape. Yes, blockchain can solve a lot of problems, but also has some major limitations.

First off, blockchain COULD as a system in itself have a strong carbon footprint because it requires dedicated mining farms which consume a lot of electricity. Unfortunately, there are no exact estimates of how much power bitcoin really uses. The numbers are spread over a very wide range, depending on the methodology used and timing of predictions.

Second, a fundamental issue with carbons markets, measuring carbon emissions, cannot be directly solved with a blockchain. An immutable ledger can record emissions and store information, but it cannot assess whether the information provided was accurate.

The Use of Oracles

To solve this issue, artificial intelligence and sensor technology can help. However, blockchains cannot access data outside their network, which is where an agent called an oracle comes into play.

According to blokchainhub.com, “An oracle, in the context of blockchains and smart contracts, is an automated virtual agent that finds and verifies real-world occurrences and submits this information to a blockchain to be used by smart contracts.” Upon the submission of information, a particular value is reached, leading to a change in the state of contract based on predefined algorithms and thus, triggering an event on the blockchain.

For carbon sequestration, an oracle would provide information on actual carbon emissions of an entity. Following the receipt of this information, the entity will be issued coins on a trading system, reducing the need for third-party verification.

Such a system, however, is heavily reliant on the quality and accuracy of the sensors used, along with the costs that are associated with the installation of such sensors. Nonetheless, an oracle-based carbon sequestration system is definitely the right step towards creating an ideal carbon trading environment.

Will This Perfect Situation Ever Exist?

In October 2017, the Manitoba Government announced the possibility of a carbon tax to offset rising hydro rates for low-income earners. This somewhat alludes to the fact that these older strategies are not likely to disappear anytime soon, and the future could be a mish-mash of different carbon schemes. A need to connect all these markets might arise to create an efficient global system – a situation where a multidisciplinary approach of IoT, artificial intelligence and blockchain will again come in handy.